Carmelo Arden Quin // Paintings, Collages, Mobiles, 1930s-1970s

Carmelo Arden Quin // Paintings, Collages, Mobiles

Works from the 1930s to the 1970s

Sicardi Gallery, Houston, TX USA

When Carmelo Arden Quin (b. 1913, Uruguay) and artists Gyula Kosice, Rhod Rothfuss, and Tomás Maldonado produced the single-issue art and literary magazine Arturo in 1944, they articulated a desire shared by many young artists in Buenos Aires: to create a movement that would break free from the visual traditions of the past and move away from the “fictions” of representation. In manifestoes, poems, essays, and images, the magazine’s contributors described an abstract art for a new age. Arturo’s authors would go on to launch several abstract art movements in Argentina, including the Asociación de Arte Concreto-Invención and Perceptismo. And, shortly after Arturo appeared, Arden Quin co-founded the Madí group.

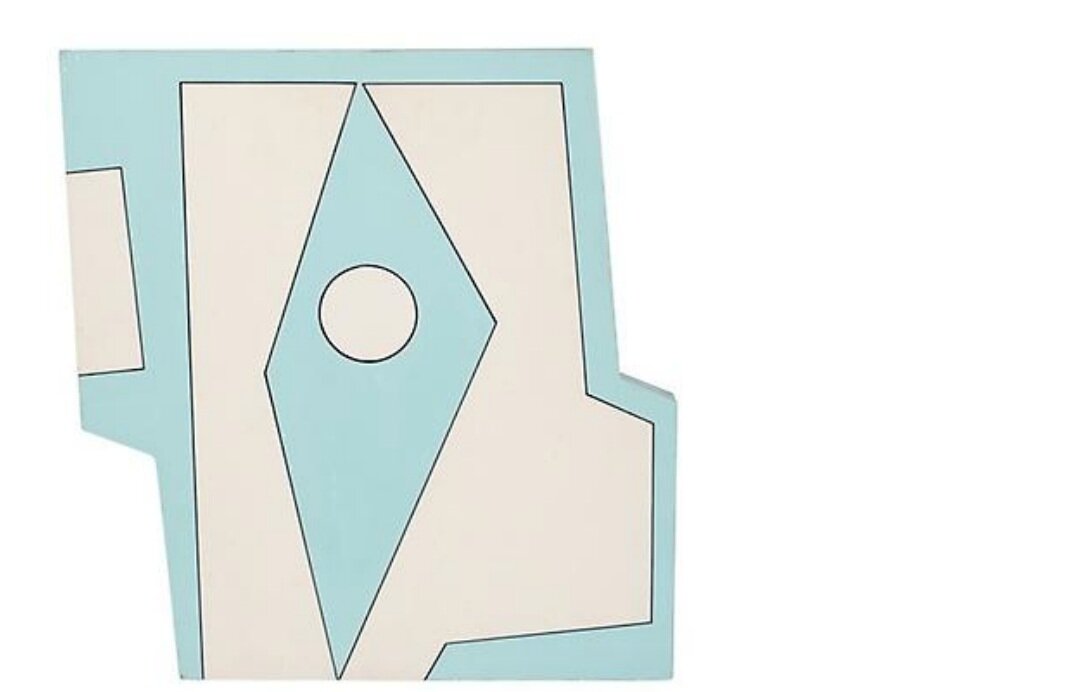

Characterized by irregularly-shaped frames, blocks of unmixed colors, and individually articulated pieces, Madí paintings often evoke a playful whimsy. Arden Quin’s painting Madi IIA (1945), for example, fits within a frame that is almost rectangular, except for a small, sharp jag on both the left and right sides. Painted in oil on cardboard, the work includes two central shapes, somewhat circular, which are painted on a white polygonal ground. The objects are unidentifiable, and their ambiguity was precisely what interested Arden Quin. By making non-representational forms, he developed paintings that could exist as entirely self-referential objects. Speaking in 1945, Arden Quin notes, “For us, the use of polygons, either as the forms themselves or as a boundary within which the composition is set, is what separates us, what gives us originality. By abandoning the four classic orthogonal angles—the square and rectangle—as a basis for composition, we have increased the possibilities for invention of all kinds.”

For the artists in the Madí group, the material nature of the physical object was of primary importance. By breaking away from the rectangular frame, they transcended the effect of a window view, and they made something that referenced only itself: a singular new creation. Curator Mari Carmen Ramírez writes, “The ‘structured’ frame…individualizes Madí’s painted constructions, establishing their difference, their particular rhythm, as well as their vital spark.”[1]

The earliest work in the exhibition dates to 1936, one year after Arden Quin first met his mentor Joaquín Torres-García. Having returned to Montevideo in 1934 after more than 40 years in Europe and the United States, Torres-García introduced the young Arden Quin to the works of Kasimir Malevich, Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and the Cercle et Carré group. Arden Quin would later recall that his meeting with Torres-García was the motivating factor behind his decision to become an abstract artist. In Diagonel des Carrès (1936), Arden Quin painted a multicolored diagonal line of squares leading across two paired rectangles (within which are several variations of quadrilateral forms). The pink square at the lowest point of the diagonal line lands a few inches away from the painting’s border, leaving a visual tension in the gap between the line and the rectangle’s border. Diagonel des Carrès was made the same year Arden Quin showed his work for the first time, in a group show in support of the Spanish Republic.

In 1944, Torres-García published his book Universalismo constructivo, and that year he also contributed a drawing, a poem, and a short text to the Arturo magazine. Inspired in part by Torres-García’s construction of wooden toys with parts that could be rearranged, in the 1940s Arden Quin began to develop paintings with articulated structures and, occasionally, movable pieces. In his “coplanals,” he explored the cooperative relationships between planes that could be moved freely in space (as opposed to planes confined within frames). Coplanal Colgante (1949) and Movile (1950) demonstrate Arden Quin’s sustained attempts to escape the picture plane. In these works, Arden Quin also demonstrates one of Madí’s most important ideals: dynamic movement made evident through metamorphosis, rotation, or subtle shifts. Like the mobiles, the paintings with irregular borders also suggested movement; by transforming the edges of the paintings into unpredictable shapes, Madí artists made the borders function as active presences in the work.

In 1946, the Madí members showed their work in two important exhibitions at the homes of Dr. Enrique Pichón Rivière, an art patron for the avant-garde, and Grete Stern, a Bauhaus-trained photographer living in Buenos Aires. Speaking at Pichón Rivière’s home in 1946, Arden Quin argued for the mobility and dialectical nature of Madí art and for the expansion of Madí into many forms of creative endeavor: “Let us make mobile the volumes, mobile the planes and colors… Let us make painting mobile, sculpture mobile, architecture mobile, the poem mobile, and thought dialectical…” Madí exhibitions, characterized by salon-style installation, also included poetry readings, dance performances, and music.

In 1947, the original Madí group split over ideological and aesthetic differences between Arden Quin and Gyula Kosice. When he moved to Paris in 1948, Arden Quin began an international branch of the group, while Kosice continued Madí activities in Buenos Aires.

Paris provided Arden Quin with a wealth of new opportunities. In 1948, he participated in the Paris Salon des Réalités Nouvelles for the first time; within three years, the Salon devoted an entire room to Madí work. In Paris, Arden Quin met Jesús-Rafael Soto, and invited him to participate in a group exhibition titled Espace Lumière (Light Space) in late 1951. Soto shared some of the Madí group’s interests in introducing movement to abstraction, engaging the viewer, and making work that was not centered upon the artist’s subjectivity. Arden Quin also connected with artists Constantin Brancusi, Francis Picabia, Michel Seuphor, Jean Arp, and Georges Braque, among others. He returned briefly to Buenos Aires in the early 1950s, where he co-founded the Asociación Arte Nuevo with Aldo Pellegrini. In 1958, Arden Quin moved permanently to Paris.

In the 1950s, Arden Quin introduced collage and decoupage to his works, and he continued to explore these media until the early 1970s. Collage offered Arden Quin a new range of textures and materials and a new process with which he could develop his compositions. In two untitled collages from 1962, Arden Quin works with an earthy palette, layering ink and paper into new shapes that connect in a delicate balance with one another.

Throughout the 1950s, Arden Quin was in close contact with other artists, and he participated in many collective and solo exhibitions. Uruguayan poet Volf Roitman created the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Madistas in Arden Quin’s studio, and artists and writers frequented the space. Among these, Arden Quin especially admired the Belgian painter Georges Vantongerloo, who encouraged Arden Quin to use more white in his paintings. Fleurs, Hommage à Vantongerloo (1950), Losange Bleu (1952) and Damier Amovible, Collage, Plastique (1956) demonstrate the important shift in Arden Quin’s use of color: in these, he works with white and black, as well as light shades of primary colors to make alternately geometric or organic compositions. In each of these, he also continued to alter the shapes and surface of his picture plane: these are painted on highly polished enameled wood he called plastiqu blanche (white plastic).

A series of three acrylic paintings on wood, which Arden Quin described as forme galbée (curved shapes), show another compositional exploration. In Forme Galbée, Galbée s/t, and Galbée Serie “H” (all 1971) Arden Quin painted patterns of lines, squares, and circles across the shaped wood ground. The gentle undulation of the surface makes the lines seem to vary from straight to angled or wavy depending upon where the viewer stands.

By the 1970s, Arden Quin’s work was being exhibited often in France and Argentina. Among many other exhibitions, his work was included in Vanguardias de la década del 40: Arte Concreto-Invención, Arte Madí, Perceptismo at the Museo de Artes Plásticas Eduardo Sívori (1980), Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1993), Heterotopías: Medio Siglo sin Lugar, 1918-1968 at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (2000), and Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2004). Carmelo Arden Quin died in 2010, at his home in Savigny-sur-Orge, near Paris.

Laura August, PhD

2013

[1] Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Vital Structures: The Constructive Nexus in South America.” In Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.